Module XX: Power 2 (Unlimited Power)

Learning goals

- Compare analytic power methods with power simulations.

- Be able to draw simulated power curves for complicated models

Calculating power

- For this example, we’ll use birthweight data from the

MASSpackage, calledbirthwt. You can load this data using thedata()function.

- Let’s do a two sample \(t\)-test for birth weight (

bwt) for mothers who smoke and don’t smoke (smoke).

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: bwt by smoke

t = 2.7299, df = 170.1, p-value = 0.007003

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group 0 and group 1 is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

78.57486 488.97860

sample estimates:

mean in group 0 mean in group 1

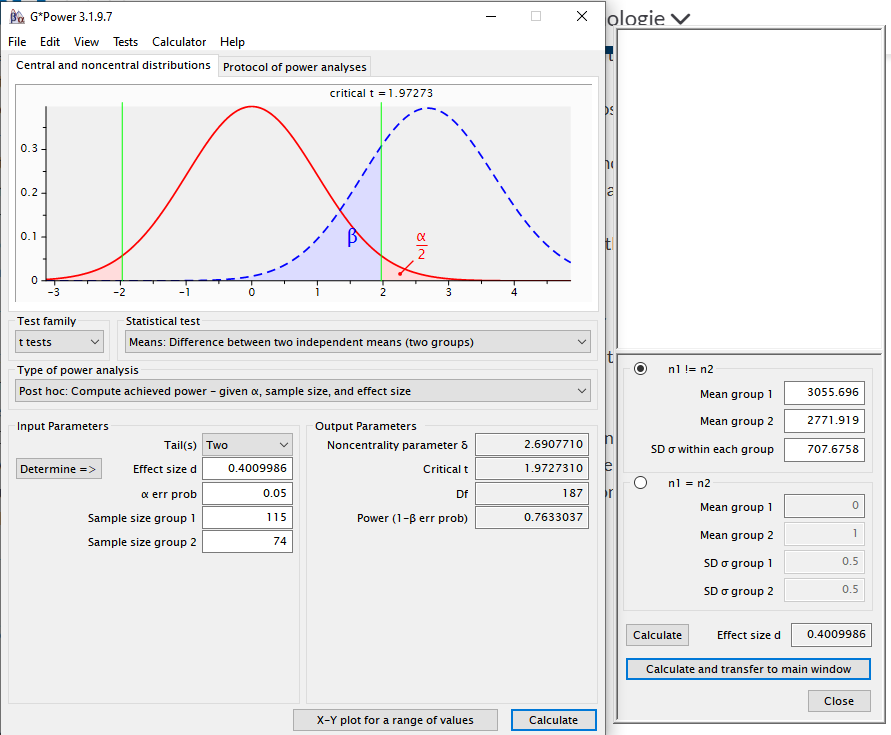

3055.696 2771.919 - We can also calculate the power of this test. It takes a little bit of finagling, but it’s not too hard.

- You could also use G Power to do this, and it would probably be easier.

- Side note: aggregate is a great way to use formulas for grouped calculations.

group_sample_sizes <- aggregate(bwt ~ smoke, data = birthwt, FUN = length)

group_means <- aggregate(bwt ~ smoke, data = birthwt, FUN = mean)

group_sds <- aggregate(bwt ~ smoke, data = birthwt, FUN = sd)

power.t.test(

# Use the average group sample size

n = mean(group_sample_sizes$bwt),

# d = TRUE difference in means / so we use our post-hoc observation

delta = diff(group_means$bwt),

# Pool the SD's

sd = sqrt(mean(group_sds$bwt ^ 2)),

# Alpha level of test

sig.level = 0.05,

# Details about the test

type = "two.sample",

alternative = "two.sided"

)

Two-sample t test power calculation

n = 94.5

delta = 283.7767

sd = 707.6758

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.7829694

alternative = two.sided

NOTE: n is number in *each* group- We can an estimated power of about 78%. Of course this is post-hoc power so it’s basically useless.

- The G Power calculation is actually a bit more flexible.

- The estimate is a bit different because of how G Power deals with unequal sample sizes between groups.

The real power of power

- Power is much more useful when it isn’t post-hoc. That is, we should use power to plan our studies, rather than calculate the power after we do a test.

- The most common application of power is sample size estimation.

- If we want to do a t-test between two groups, we can calculate the sample size we need to achieve a specific power and alpha level for a test, assuming some underlying effect size and variability.

- For a study that requires an unpaired t-test, let’s calculate the required sample size to achieve typical targets of \(\alpha = 0.05\) and \(1 - \beta = 0.8\). For this example we’ll assume that our effect is standardized, so a clinically meaningful effect size is \(0.1\). We’ll assume for this example that the SD is \(0.25\).

- Hint: you need to specify different arguments in

power.t.test()this time.

- Solution: we need about 100 people in each group, so 200 total.

power.t.test(,

delta = 0.1,

sd = 0.25,

sig.level = 0.05,

power = 0.80,

# Details about the test

type = "two.sample",

alternative = "two.sided"

)

Two-sample t test power calculation

n = 99.08057

delta = 0.1

sd = 0.25

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.8

alternative = two.sided

NOTE: n is number in *each* group- What if we don’t know the effect size or standard deviation?

Power curves

- We can often get a good idea about the SD from the literature or from knowledge about how our assay/measurement works, so we’ll ignore that for now (it is harder for observational studies than for experiments).

- But in general we have no idea what the effect size (difference in means) should be before we do the study. So how do we get the power or sample size?

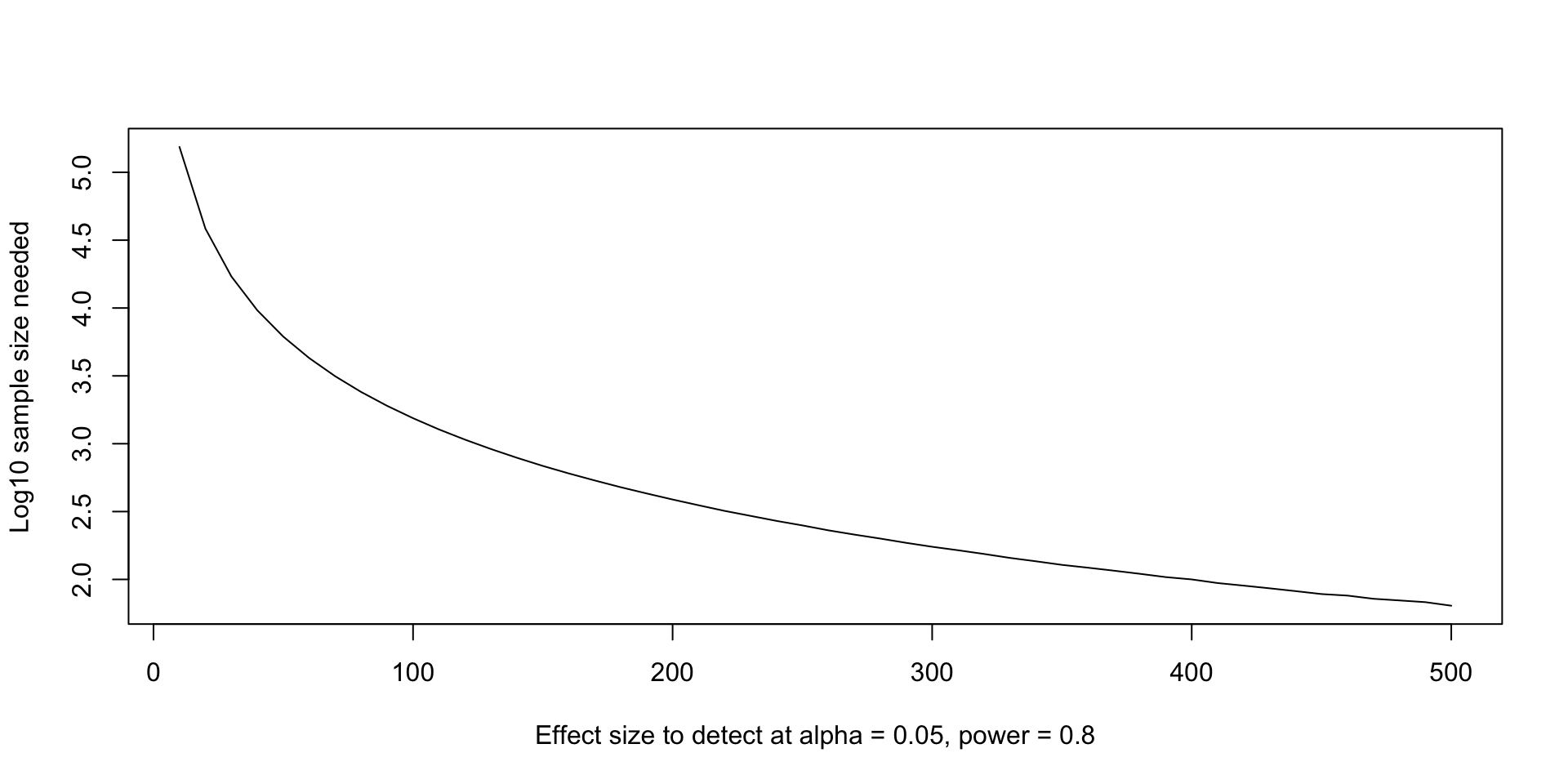

- We can calculate the required sample size to achieve multiple different effect sizes. For the

birthwtexample, let’s pretend we didn’t run our study yet, but we know that the pooled sd should be around 700. Let’s calculate the sample size needed to achieve 80% power at multiple effect sizes. - In real life, maybe we can get this magical 700 number from previous studies or preliminary data.

- We can use the tools we’ve learned to get many different sample size calculations.

effect_sizes <- seq(10, 500, 10)

sample_size_calc <- lapply(

effect_sizes,

\(d) power.t.test(delta = d, sd = 700, sig.level = 0.05, power = 0.80)

)

str(sample_size_calc, 1)List of 50

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"

$ :List of 8

..- attr(*, "class")= chr "power.htest"- But how do we get the sample size out of each power object thing? Fortunately

power.t.test()returns an S3 object of classpower.htest, and the documentation tells us how to get the quantities we want. - We also want to round the estimate up to the nearest whole number and (optionally, but I prefer this) multiply by two for the total sample size.

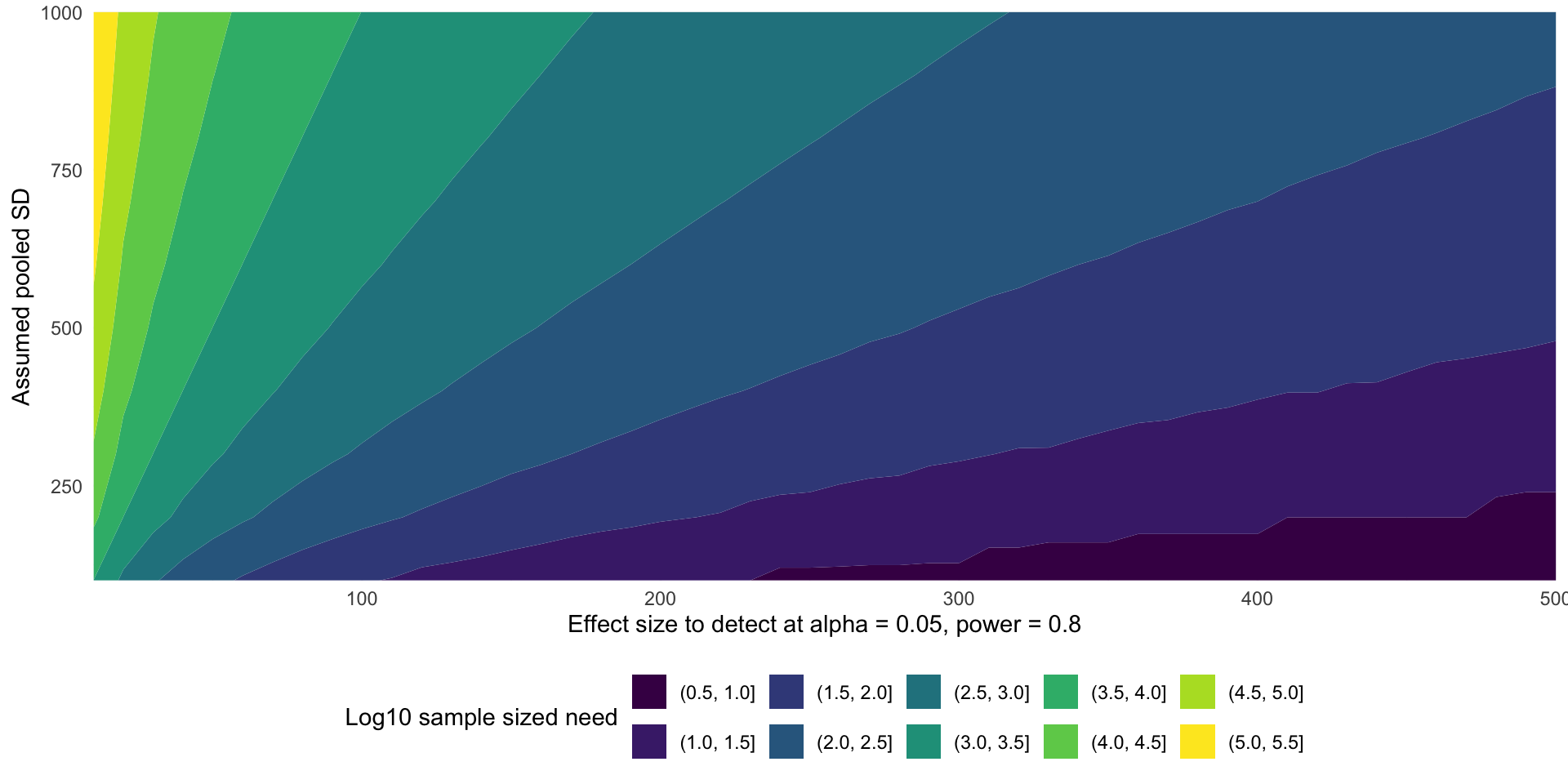

You try it! Power contours

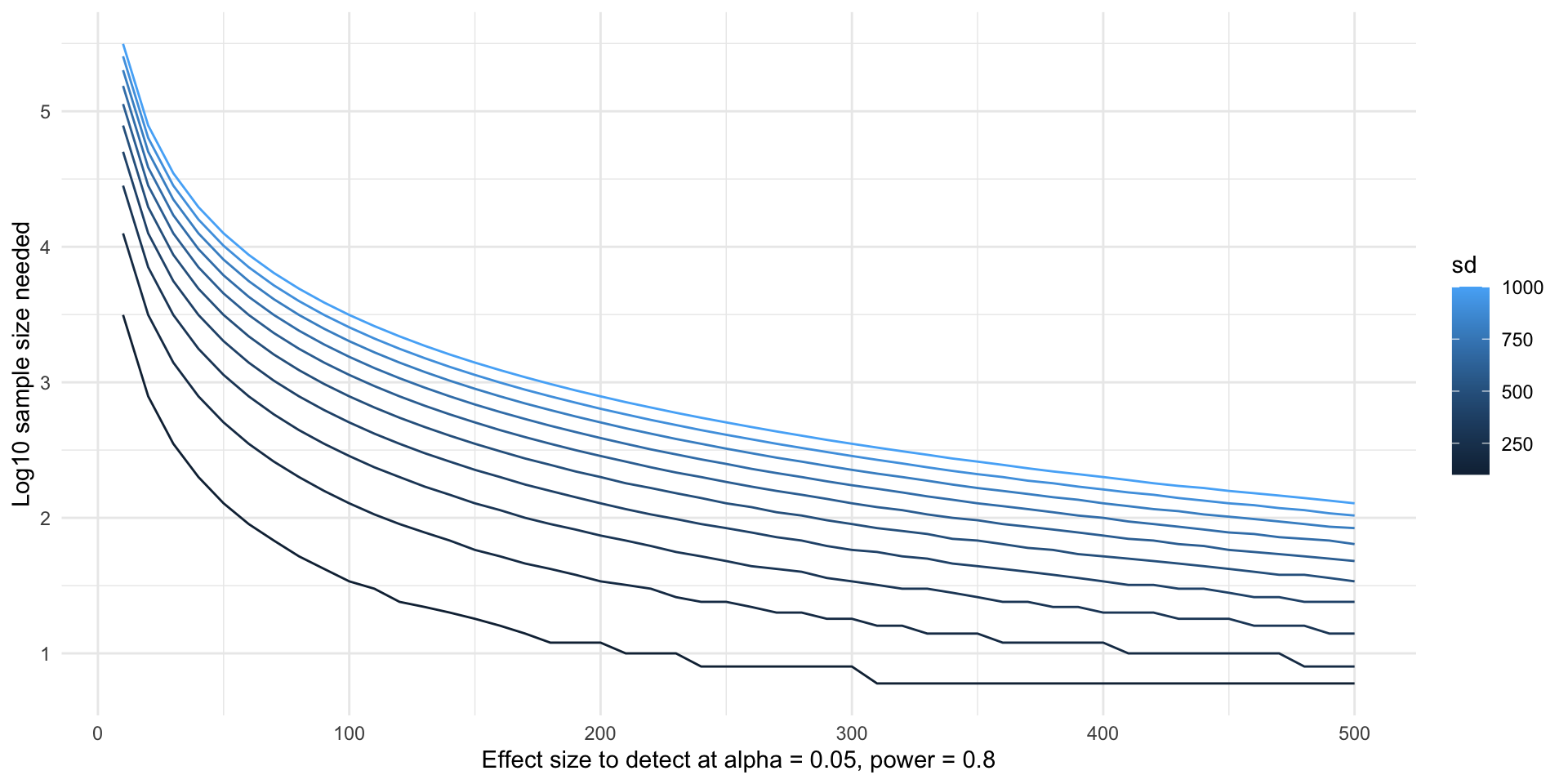

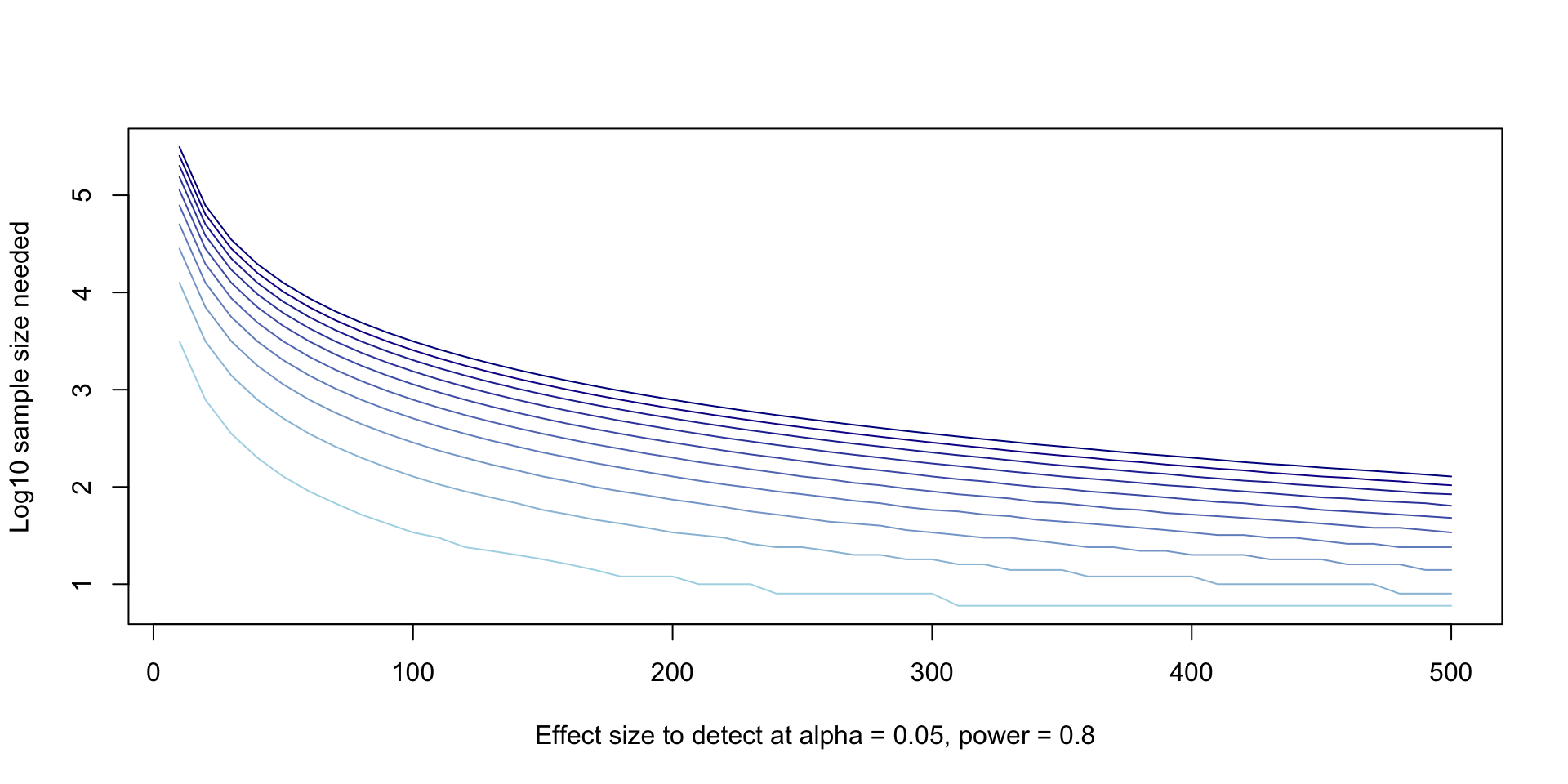

- If we’re willing to do a little bit more wrangling, we can also do this for multiple variances.

- Here’s some code to help you get started, and then you can try to calculate the sample sizes yourself. First, make a grid of all the effect size and variance combinations we want to try.

- Note that the more values of delta and SD you want to try, the grid can become huge really quickly which could take a long time to run.

- Now because they are in a grid, you can do a 1-dimensional loop or

lapply(), instead of having to do a nested one, just iterate over the number of rows in the grid.

- My solution:

- There are two main ways people will try to plot these curves. One is by plotting a different colored curve for each SD.

plot(

NULL, NULL,

xlim = range(effect_sizes),

ylim = range(log10(power_variables$sample_size)),

xlab = "Effect size to detect at alpha = 0.05, power = 0.8",

ylab = "Log10 sample size needed",

type = "l"

)

variance_levels <- unique(power_variables$sd)

colors <- colorRampPalette(c("lightblue", "darkblue"))(length(variance_levels))

for (i in 1:length(variance_levels)) {

sub <- subset(power_variables, sd == variance_levels[[i]])

lines(x = sub$delta, y = log10(sub$sample_size), col = colors[[i]])

}

- If you know

ggplot2, this is way easier inggplot2.

- Mathematicians love to plot this as a “contour plot”. These are basically impossible to read but look impressive.

- This is insanely annoying to do in base R, so I’ll only show it in

ggplot2.

ggplot(power_variables) +

aes(x = delta, y = sd, z = log10(sample_size)) +

geom_contour_filled() +

coord_cartesian(expand = FALSE) +

labs(

x = "Effect size to detect at alpha = 0.05, power = 0.8",

y = "Assumed pooled SD",

fill = "Log10 sample sized need"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

Power simulations

- Power calculations are “non-analytic” for nearly all hypothesis tests, except for very simple ones.

- Simulation is a much more robust way to estimate power, because it works for any test.

- As an example, we’ll first walk through simulating the power for the same t-test we just did.

- Remember that power is the chance that a false null hypothesis will be rejected.

- Choose the parameters for the simulation. These include all of the TRUE parameters for the data we hope to collect, the significance level, and the number of simulations.

- Now we generate

N_simsnumber of datasets from a model described by the \(t\)-test: that is, we drawn1observations from a normal distribution wiht meanmu1and sdsd1, and likewise for group 2.

simulate_one_dataset <- function(n1, n2, mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2) {

group1_y <- rnorm(n1, mu1, sd1)

group2_y <- rnorm(n2, mu2, sd2)

out <- list(group1 = group1_y, group2 = group2_y)

return(out)

}

# replicate() is just a fancy way to use lapply() when the function

# you want to repeat doesn't depend on any iteration-specific argument

simulated_data <- replicate(

N_sims,

simulate_one_dataset(n1, n2, mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2),

# Set simplify = FALSE or you get a weird array thats hard to understand

simplify = FALSE

)- Now we do a (Welch’s two-sample) t-test on each simulated dataset. Note that in our true data generating process, the null hypothesis is always false by design. (This is one of the times where it’s easier NOT to use a formula!)

- Now we count the t-tests that correctly rejected the null hypothesis, i.e. \(p \leq \alpha\).

- Now we calculate the power of our test as the probability that a simulated test rejected H0. Note that we even compute a confidence interval for our power here, although its interpretation is a bit tricky it can tell us a range of powers that are consistent with our simulation.

# We can use this function to get the exact CI (Clopper-Pearson) for us

# Just ignore the p-value, it doesn't make sense!!

binom.test(sum(rejected_h0), N_sims)

Exact binomial test

data: sum(rejected_h0) and N_sims

number of successes = 8227, number of trials = 10000, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.5

95 percent confidence interval:

0.8150708 0.8301408

sample estimates:

probability of success

0.8227 - Interpretation: the power of our test after 10,000 replicates was about 83%, and our CI is pretty tight around this number. If this wasn’t post-hoc, we would say that the planned sample sizes achieve our goal of \(80\%\) power at \(\alpha = 0.05\).

You try it!

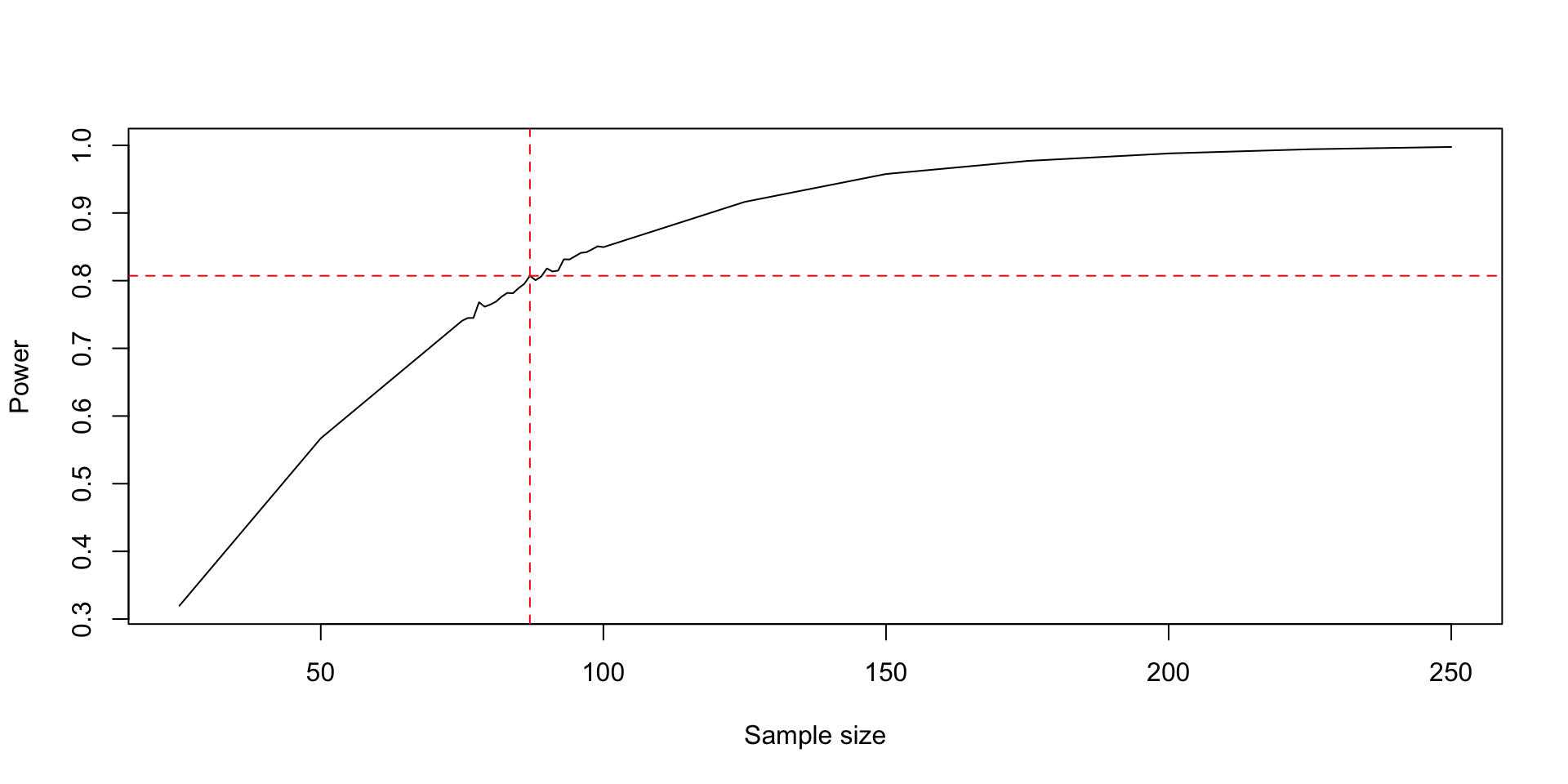

- More often, we want to know what sample size it takes to get 80% power for a fixed leve

- The only way to do this by simulation is to try many sample sizes and do a simulation for each one.

- For the t-test example (this time you can assume the sample size for the two groups is the same to make life easier), make a plot of power vs. sample size, using the same group means and group SDs.

- Hint: write a function that simulates the data, does the t-tests, and gets which tests are rejections. Then,

lapply()this function over multiple values ofn(this is easy if you assumen1andn2are equal).

- Hint: here’s an outline for my function, and the code for how I used it.

- I returned the entire vector of TRUE/FALSE for rejections from the function, because I thought this was a convenient way to handle the data. You can do the sum() or mean() inside of the function and return a single number if you prefer that.

simulate_t_test_power <- function(N_sim, n1, n2, mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2, alpha = 0.05) {

simulated_data <-

replicate(

N_sims,

simulate_one_dataset(n1, n2, mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2),

simplify = FALSE

)

simulated_t_tests <- lapply(

simulated_data,

\(d) ...

)

simulation_p_values <- sapply(simulated_t_tests, ...)

rejected_h0 <- ...

return(rejected_h0)

}

n_per_group <- seq(...)

t_test_n_simulations <- sapply(

n_per_group,

\(n) simulate_t_test_power(

1000,

n, n,

mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2

)

)- Hint: after I ran this function, here’s how I got the power for each sample size.

- Here’s my solution.

simulate_t_test_power <- function(N_sim, n1, n2, mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2, alpha = 0.05) {

simulated_data <-

replicate(

N_sims,

simulate_one_dataset(n1, n2, mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2),

simplify = FALSE

)

simulated_t_tests <- lapply(

simulated_data,

\(d) t.test(d$group1, d$group2, conf.level = alpha)

)

simulation_p_values <- sapply(simulated_t_tests, \(x) x$p.value)

rejected_h0 <- simulation_p_values <= alpha

return(rejected_h0)

}

# You can do less of these

# and make N_sim lower

# if this takes too long

n_per_group <- seq(25, 250, 25)

set.seed(102)

t_test_n_simulations <- sapply(

n_per_group,

\(n) simulate_t_test_power(

1000,

n, n,

mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2

)

)

# sapply() gives us a matrix that we can easily apply() on to get summaries

# or use colMeans() cause its super fast and easy

res <- colMeans(t_test_n_simulations)

res [1] 0.3197 0.5670 0.7407 0.8495 0.9164 0.9576 0.9769 0.9880 0.9942 0.9976- By looking at these results, it’s clear where we can do a second simulation to hone in on a better sample size – between the 3rd and 4th levement of

n_per_groupwe get to our target.

# Interpolate between those two numbers, but don't repeat them

# cause we already did those sims!

n_per_group2 <- seq(n_per_group[3], n_per_group[4], 1)

n_per_group2_trim <- n_per_group2[2:(length(n_per_group2) - 1)]

set.seed(103)

t_test_n_simulations2 <- sapply(

n_per_group2_trim,

\(n) simulate_t_test_power(

1000,

n, n,

mu1, mu2, sd1, sd2

)

)

# sapply() gives us a matrix that we can easily apply() on to get summaries

# or use colMeans() cause its super fast and easy

res2 <- colMeans(t_test_n_simulations2)

res2 [1] 0.7448 0.7449 0.7681 0.7615 0.7647 0.7690 0.7764 0.7819 0.7814 0.7889

[11] 0.7952 0.8072 0.8007 0.8061 0.8180 0.8135 0.8149 0.8316 0.8313 0.8361

[21] 0.8410 0.8420 0.8463 0.8508- Now I’ll show you a neat trick to combine these simulations together and make a plot.

all_n <- c(n_per_group, n_per_group2_trim)

all_res <- c(res, res2)

sort_order <- order(all_n)

plot(

all_n[sort_order], all_res[sort_order],

type = "l",

xlab = "Sample size", ylab = "Power"

)

# Find the smallest sample size with a power above 0.8

best_samp_size <- min(all_n[all_res > 0.8])

bss_power <- all_res[all_n == best_samp_size]

abline(h = bss_power, col = "red", lty = 2)

abline(v = best_samp_size, col = "red", lty = 2)

Setting up a power simulation for logistic regression

- Simulating power is a MUST when we need to use a more complex model. For example, we have to do simulation to get the power of logistic regression.

- I’ll walk you through the data generating code and the correct p-value to check, but I’ll let you fill in the code details.

- Recall that the model we fit for logistic regression is something like this.

\[ y_i \sim \text{Bernoulli}(p_i) \\ \text{logit}(p_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i \\ \]

- So the things we need to assume are values for \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) and the allowed values or distribution of \(x_i\). And of course we need a sample size \(n\) that we’ll vary to see how the power changes.

- We can interpret \(\beta_0\) as the log-odds of the event occurring for an individual at baseline. Let’s assume our outcome is somewhat rare, say \(10\%\) of people get it. We can convert this to log-odds with some R code.

- So we’ll say \(\beta_0 = -2.2\).

- Now we need to assume values for \(x\) and an effect size \(\beta_1\). For simplicity, let’s say \(x\) is dichotomous, and if an individual has the exposure \(x=1\), their log-odds are \(1.5\times\) the log-odds of someone with \(x=0\), which means \(\beta_1 = 1.5\).

- Finally, since \(x\) is dichotomous, we need a baseline prevalence of \(x\). Let’s say the prevalence of \(x\) is \(40\%\), pretty common but not quite half and half.

- So then we can sample from the model.

generate_logistic_model_data <- function(n, beta_0, beta_1, exposure_prevalence) {

x <- rbinom(n, size = 1, prob = exposure_prevalence)

logit_p <- beta_0 + beta_1 * x

p <- plogis(logit_p)

y <- rbinom(n, size = 1, prob = p)

out <- list(x = x, y = y)

return(out)

}

set.seed(100)

test_logistic_data <- generate_logistic_model_data(100, -2.2, 1.5, 0.5)- Now let’s walk through the test we need to do.

- First we fit a glm.

test_logistic_fit <- glm(

test_logistic_data$y ~ test_logistic_data$x,

family = "binomial"

)

summary(test_logistic_fit)

Call:

glm(formula = test_logistic_data$y ~ test_logistic_data$x, family = "binomial")

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -2.7515 0.5955 -4.621 3.83e-06 ***

test_logistic_data$x 2.3461 0.6618 3.545 0.000392 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 107.855 on 99 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 89.998 on 98 degrees of freedom

AIC: 93.998

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5- From the summary output, we see that the p-value for our test of interest is \(0.000392\). How do we get that out of the test?

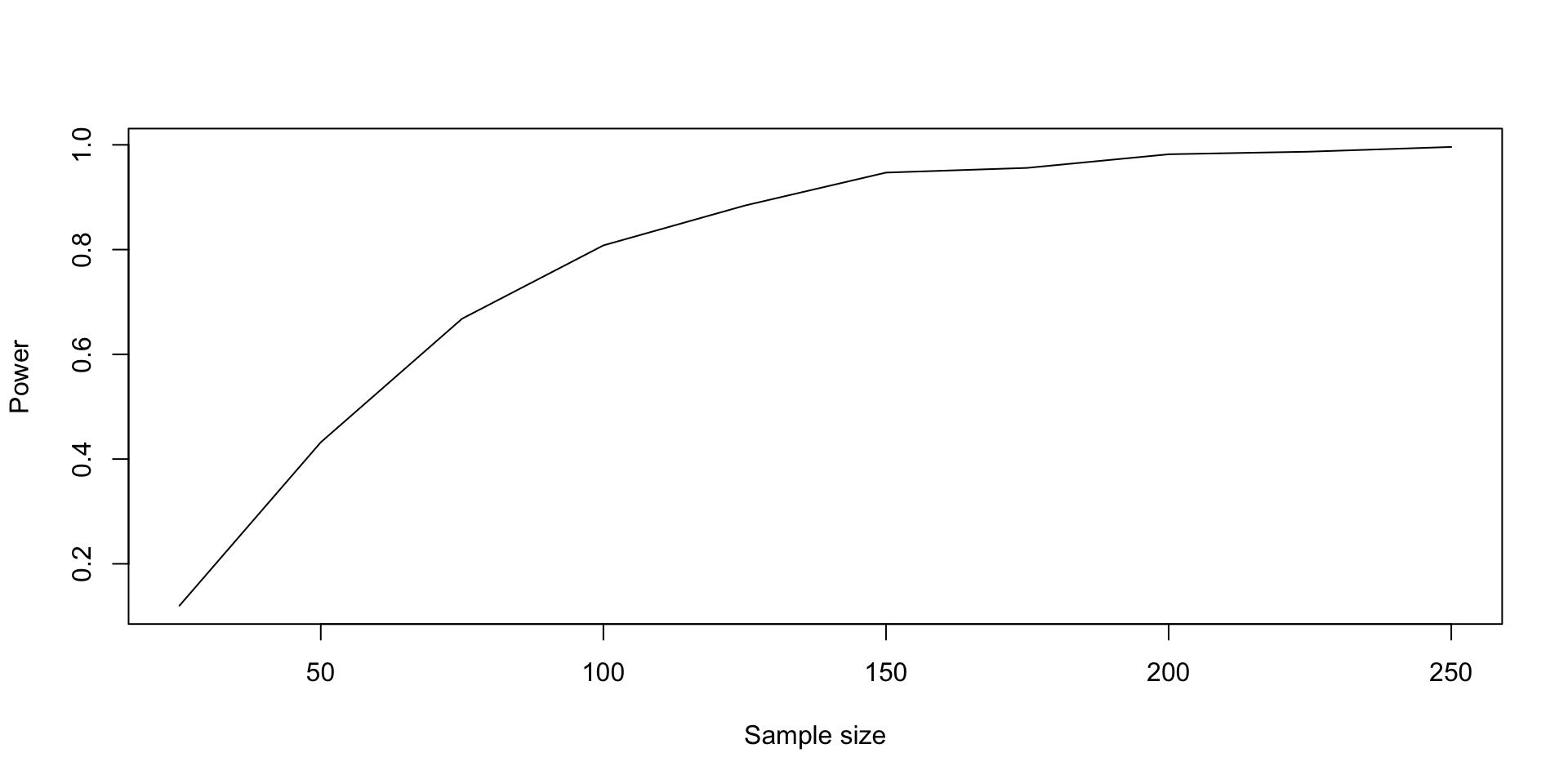

You try it! Finish the power simulation

- Now that we’ve walked through the building blocks, finish the power simulation. Find an \(n\) where the power under our assumptions about the data is between \(0.75\) and \(0.85\), that range is close enough.

- Hint: this kind of power simulation is easier if you break it down into components, write a function for each component, and then put them all together.

- I think you need three components: a data simulation function that returns a data set, a test function that returns a p-value for the given dataset (or returns accept/reject), and a function that puts those two parts together so you can repeat the whole thing.

- Hint: here’s the test function.

- Hint: now you can put the two parts together and then get the rejections.

- Hint: here’s my completed function.

- Can you repeat it for multiple

nvalues now?

logistic_power_simulation <- function(

N_sims, n, beta_0, beta_1, exposure_prevalence, alpha

) {

simulated_datasets <- replicate(

N_sims,

generate_logistic_model_data(n, beta_0, beta_1, exposure_prevalence),

simplify = FALSE

)

simulated_p_values <- sapply(

simulated_datasets,

get_exposure_slope_p_value

)

rejections <- simulated_p_values <= alpha

return(rejections)

}n_values <- seq(25, 250, 25)

set.seed(110)

logistic_sim <- sapply(

n_values,

\(n) logistic_power_simulation(

1000,

n,

-2.2, 1.5, 0.4, 0.05

)

)

logistic_sim_power <- colMeans(logistic_sim)

plot(

n_values, logistic_sim_power,

xlab = "Sample size", ylab = "Power",

type = "l"

)

- If we look at the values, we see that a sample size of 100 gives us a power of about \(81\%\) under these assumptions.

Final note: parametrizations

- Notice that in the logistic regression simulation, we simulated our dataset using the exposure prevalence. If you know the exposure prevalence, that works fine.

- If you don’t know the exposure prevalence, you can instead simulate a dataset with

n_exposedandn_unexposed, or assume the sample size of the two groups has to be equal like we did for the t-test example. - These are basically the same, we just assumed that

n_exposed / n_total = 0.4, but there’s lots of ways you can do the same thing. - In general, what matters the most for the power of a logistic regression is the number of events in each group, and you can write a simulation that takes that into account too.

Summary

- Power is kind of confusing, we have to make really strong assumptions to do an a priori power analysis. But post hoc power analysis doesn’t really tell us anything.

- Calculating the power of a test directly is impossible for most tests.

- Fortunately we can use the tools we learned in this class to do a power simulation, which can help us estimate power under various assumptions for complicated models.